typhoonpilot

Well-Known Member

British airlines 'face multiple toxic air claims'

By Jim Reed Reporter, Victoria Derbyshire programme

The cases are funded by the Unite union which represents 20,000 flight staff.

Workers believe they have fallen sick after breathing in fumes mixed with engine oil and other toxic chemicals.

The Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) says incidents of smoke or fumes on planes are rare and there is no evidence of long-term health effects.

Oxygen masks

The Unite union, which is calling for a public inquiry into contaminated cabin air, has recently opened a dedicated legal unit to record and process claims from its membership.

Its lawyers are now working on 17 "definite" individual personal injury claims against British airlines in the civil courts, although these are still at an early stage.

Uncensored safety reports submitted to the CAA, and obtained by the Victoria Derbyshire programme, show that between April 2014 and May 2015 there were 251 separate incidents of fumes or smoke inside a large passenger jet operated by a British airline.

The BBC has, where possible, chosen not to include cases which could be blamed on an internal fault like a broken toilet or air conditioning system.

The statistics do not include international airlines, such as Lufthansa and Ryanair, even when travelling in British airspace.

An illness was reported in 104 of the 251 cases, and on at least 28 of those flights oxygen was administered.

The programme has also seen first-hand testimony from a pilot working for a major UK airline who believes he was affected by toxic fumes while landing at Birmingham Airport in 2014.

"Almost instantly myself and the captain became very unwell and decided it was bad enough to place our oxygen masks on," he said.

"We didn't declare a mayday - mostly due to not being able to think of the words needed to say - and ended up auto-landing the plane and simply briefing, 'Whoever is alive or conscious, pull back the thrust levels after touchdown.' It was that serious."

Alleged health risks explained

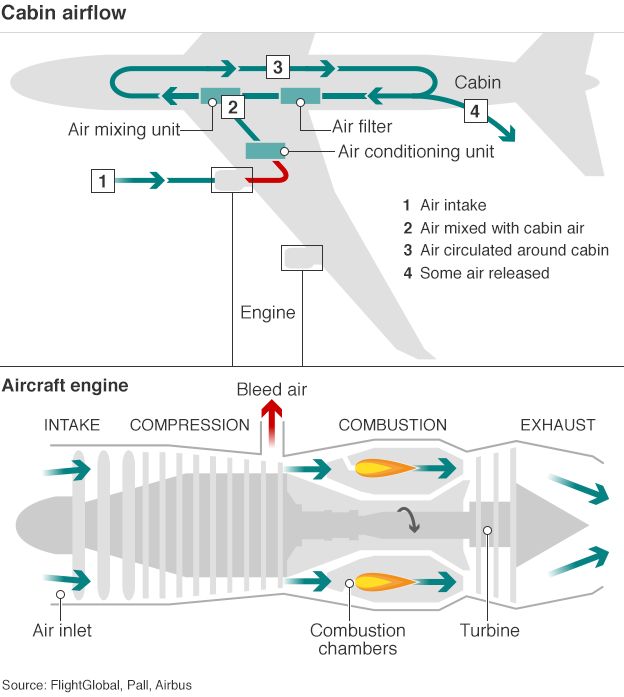

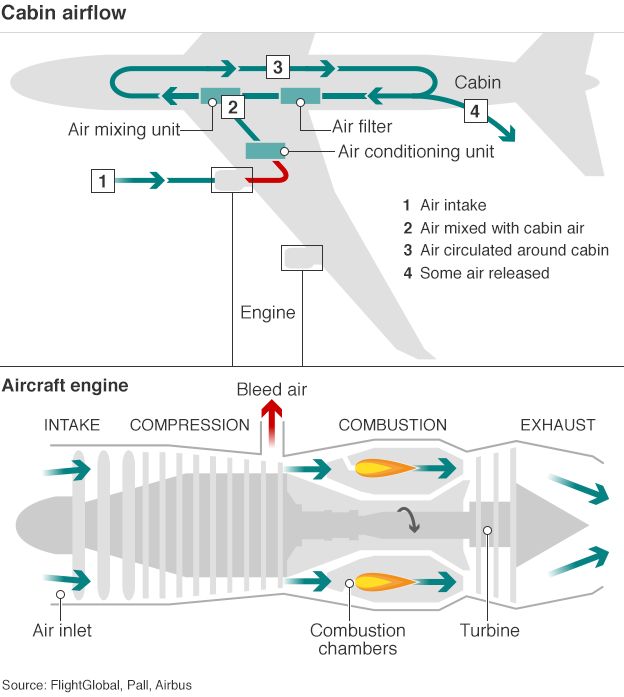

Around half the air on board most modern commercial jets is drawn through the engines.

Campaigners say when a fault occurs in the engine seals, a cocktail of potentially poisonous gases can reach the cabin. This includes TCP, an organophosphate known to be dangerous to human health in high enough quantities.

It is repeated exposure to such fume events - combined with long-term, low-level exposure to chemicals - which some cabin crew believe has damaged their long-term health.

The problems are said to affect the central nervous system and brain.

The CAA says there is no evidence that chemicals appear at high enough concentrations to cause harm.

How safe is air quality on planes?

Lawyers and campaigners are closely watching a series of inquests which could influence the outcome of a much larger number of civil cases.

Pilot Richard Westgate died in December 2012, aged 43, after complaining of long-term health problems.

Last February, the coroner in the inquest into his death wrote to British Airways and the CAA saying that examinations of Mr Westgate's body "disclosed symptoms consistent with exposure to organophosphate compounds in aircraft cabin air".

He asked them to take "urgent action to prevent future deaths".

Both organisations have since replied to the coroner implying he overstepped the mark and had relied on "selective and contentious evidence".

A second inquest is due to open into the case of 34-year-old Matthew Bass who died suddenly in January 2014 after suffering unexplained health problems.

His family says a specialist post-mortem examination found high levels of toxins in his nervous system linked to organophosphates.

British Airways said in a statement: "We would not operate an aircraft if we believed it posed a health or safety risk to our customers or crew.

"There has been substantial research into questions around cabin air quality over the last few years. In summary, the research has found no evidence that exposure to potential chemicals in the cabin causes long-term ill health".

Airbus and Boeing both maintain cabin air is safe to breathe.

'Nocebo effect'

In 2013, an independent group of scientists, the Committee on Toxicity, looked at the evidence of long-term health effects for the government.

It could not establish a link between contaminated cabin air and ill health.

"The levels [of harmful chemicals in planes] were as low or even lower than those in the home or the workplace," said Prof Alan Boobis, current chairman of the committee.

"We can't be sure what the levels are in fume events, which are very rare, but we do have some information which would indicate that even in those circumstances levels are probably below those which would affect health in humans."

The committee believes one explanation could be the so-called "nocebo" effect, a psychological condition where exposure to a harmless substance can lead to nausea, fatigue and other medical symptoms.

Recorded incidents

The following table shows extracts of some of the most critical safety reports submitted by crew to the CAA.

Date Airplane Title Details

12/08/2014 Boeing 767-300 Mayday declared and aircraft returned due to acrid fumes on flight deck. Decision taken to return to departure airport. Fireman on entry stated acrid smell was obvious and strong. Captain made a PA informing customers we would be returning to departure airport due to a technical problem, but he didn't want to give them too much information on the incident... Heathrow.

13/08/2014 Airbus A320 Fumes in the flight deck caused flight crew illness. Two crew members donned portable oxygen as a safety precaution. Cabin crew members suffered stinging eyes, burning on the inside of the nose and a strong metallic taste in the mouth. Crew members attended hospital for the effects of the fumes. Praga/Ruzyne

02/11/2014 Boeing 777-200 Fumes in passenger cabin during cruise. Strong smell of gas in cabin around door area. Had previously felt sick whilst in bunk rest. I got severe headache and pain in sinus. Earlier two other flight crew had both felt nauseous and another had bad headache.

29/02/2015 Boeing 747 Fumes in cabin. Eleven of the cabin crew became unwell during the flight with symptoms of light headedness, nausea and sea sickness. Oxygen administered. During the cruise, SCCM ['Senior Cabin Crew Member] informed the Captain that a number of cabin crew were feeling unwell... One cabin crew member subsequently collapsed and was administered first aid and oxygen... A general view of incapacitation during flight for all operating crew members needs to be undertaken to ensure the existing processes remain relevant.

19/04/2015 Airbus A321 Flight crew and cabin crew illness due to fumes in the flight deck and cabin. On return sector, fumes entered flight deck from unknown origin. Both crew suffered to some degree with headaches, stinging eyes, and debilitation. One crew member remained on portable O2, which helped massively.

By Jim Reed Reporter, Victoria Derbyshire programme

- 8 June 2015

The cases are funded by the Unite union which represents 20,000 flight staff.

Workers believe they have fallen sick after breathing in fumes mixed with engine oil and other toxic chemicals.

The Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) says incidents of smoke or fumes on planes are rare and there is no evidence of long-term health effects.

Oxygen masks

The Unite union, which is calling for a public inquiry into contaminated cabin air, has recently opened a dedicated legal unit to record and process claims from its membership.

Its lawyers are now working on 17 "definite" individual personal injury claims against British airlines in the civil courts, although these are still at an early stage.

Uncensored safety reports submitted to the CAA, and obtained by the Victoria Derbyshire programme, show that between April 2014 and May 2015 there were 251 separate incidents of fumes or smoke inside a large passenger jet operated by a British airline.

The BBC has, where possible, chosen not to include cases which could be blamed on an internal fault like a broken toilet or air conditioning system.

The statistics do not include international airlines, such as Lufthansa and Ryanair, even when travelling in British airspace.

An illness was reported in 104 of the 251 cases, and on at least 28 of those flights oxygen was administered.

The programme has also seen first-hand testimony from a pilot working for a major UK airline who believes he was affected by toxic fumes while landing at Birmingham Airport in 2014.

"Almost instantly myself and the captain became very unwell and decided it was bad enough to place our oxygen masks on," he said.

"We didn't declare a mayday - mostly due to not being able to think of the words needed to say - and ended up auto-landing the plane and simply briefing, 'Whoever is alive or conscious, pull back the thrust levels after touchdown.' It was that serious."

Alleged health risks explained

Around half the air on board most modern commercial jets is drawn through the engines.

Campaigners say when a fault occurs in the engine seals, a cocktail of potentially poisonous gases can reach the cabin. This includes TCP, an organophosphate known to be dangerous to human health in high enough quantities.

It is repeated exposure to such fume events - combined with long-term, low-level exposure to chemicals - which some cabin crew believe has damaged their long-term health.

The problems are said to affect the central nervous system and brain.

The CAA says there is no evidence that chemicals appear at high enough concentrations to cause harm.

How safe is air quality on planes?

Lawyers and campaigners are closely watching a series of inquests which could influence the outcome of a much larger number of civil cases.

Pilot Richard Westgate died in December 2012, aged 43, after complaining of long-term health problems.

Last February, the coroner in the inquest into his death wrote to British Airways and the CAA saying that examinations of Mr Westgate's body "disclosed symptoms consistent with exposure to organophosphate compounds in aircraft cabin air".

He asked them to take "urgent action to prevent future deaths".

Both organisations have since replied to the coroner implying he overstepped the mark and had relied on "selective and contentious evidence".

A second inquest is due to open into the case of 34-year-old Matthew Bass who died suddenly in January 2014 after suffering unexplained health problems.

His family says a specialist post-mortem examination found high levels of toxins in his nervous system linked to organophosphates.

British Airways said in a statement: "We would not operate an aircraft if we believed it posed a health or safety risk to our customers or crew.

"There has been substantial research into questions around cabin air quality over the last few years. In summary, the research has found no evidence that exposure to potential chemicals in the cabin causes long-term ill health".

Airbus and Boeing both maintain cabin air is safe to breathe.

'Nocebo effect'

In 2013, an independent group of scientists, the Committee on Toxicity, looked at the evidence of long-term health effects for the government.

It could not establish a link between contaminated cabin air and ill health.

"The levels [of harmful chemicals in planes] were as low or even lower than those in the home or the workplace," said Prof Alan Boobis, current chairman of the committee.

"We can't be sure what the levels are in fume events, which are very rare, but we do have some information which would indicate that even in those circumstances levels are probably below those which would affect health in humans."

The committee believes one explanation could be the so-called "nocebo" effect, a psychological condition where exposure to a harmless substance can lead to nausea, fatigue and other medical symptoms.

Recorded incidents

The following table shows extracts of some of the most critical safety reports submitted by crew to the CAA.

Date Airplane Title Details

12/08/2014 Boeing 767-300 Mayday declared and aircraft returned due to acrid fumes on flight deck. Decision taken to return to departure airport. Fireman on entry stated acrid smell was obvious and strong. Captain made a PA informing customers we would be returning to departure airport due to a technical problem, but he didn't want to give them too much information on the incident... Heathrow.

13/08/2014 Airbus A320 Fumes in the flight deck caused flight crew illness. Two crew members donned portable oxygen as a safety precaution. Cabin crew members suffered stinging eyes, burning on the inside of the nose and a strong metallic taste in the mouth. Crew members attended hospital for the effects of the fumes. Praga/Ruzyne

02/11/2014 Boeing 777-200 Fumes in passenger cabin during cruise. Strong smell of gas in cabin around door area. Had previously felt sick whilst in bunk rest. I got severe headache and pain in sinus. Earlier two other flight crew had both felt nauseous and another had bad headache.

29/02/2015 Boeing 747 Fumes in cabin. Eleven of the cabin crew became unwell during the flight with symptoms of light headedness, nausea and sea sickness. Oxygen administered. During the cruise, SCCM ['Senior Cabin Crew Member] informed the Captain that a number of cabin crew were feeling unwell... One cabin crew member subsequently collapsed and was administered first aid and oxygen... A general view of incapacitation during flight for all operating crew members needs to be undertaken to ensure the existing processes remain relevant.

19/04/2015 Airbus A321 Flight crew and cabin crew illness due to fumes in the flight deck and cabin. On return sector, fumes entered flight deck from unknown origin. Both crew suffered to some degree with headaches, stinging eyes, and debilitation. One crew member remained on portable O2, which helped massively.