A Life Aloft

Well-Known Member

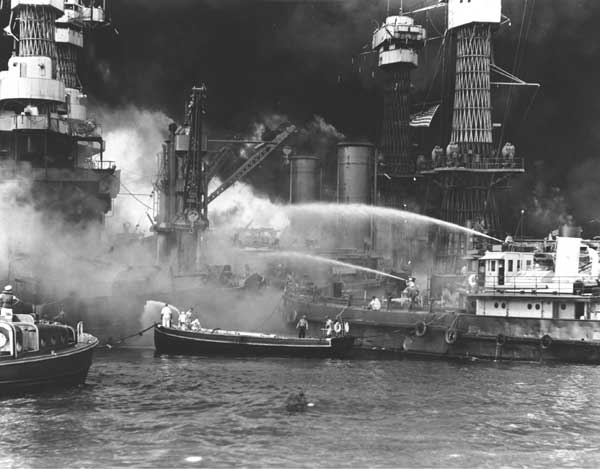

We had the opportunity to meet a few survivors from the attack on Pearl Harbor today as we went down to the USS Iowa. I have only met a handful of these survivors over the years and it is not only a honor, but a deeply humbling experience.......one that I will always treasure. Most of the men aboard these ships were just boys at the time or very young men. Yet the courage and the mettle that they showed on that terrible day is inspiring.

May their histories and stories never be forgotten.

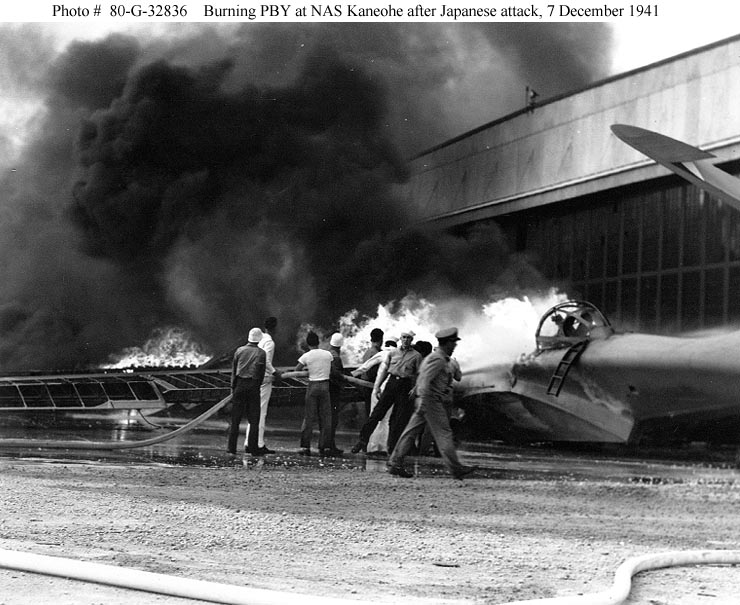

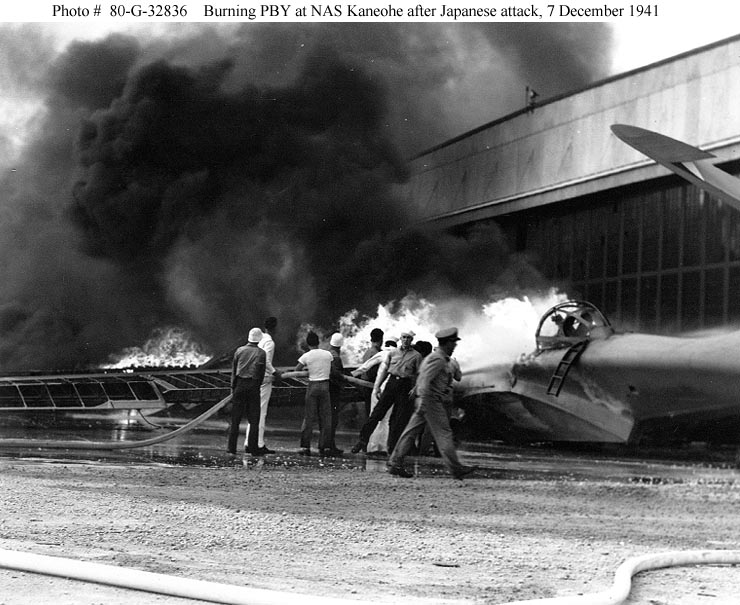

Gordon Jones and his brother Earl had been stationed at Kaneohe on December 2 1941, and yet only five days later they were to have their baptism of fire. Between the first and second wave, they were kept busy trying to extinguish fires and moving less damaged planes to safer locations. When it began, they had no reason to suspect that the second wave would be any different to the first.

Gordon recalls: 'When this new wave of fighters attacked, we were ordered to run and take shelter. Most of us ran to our nearest steel hangar . . . this bomb attack made us aware that the hangar was not a safe place to be . . . several of us ran north to an abandoned Officer's Club and hid under it until it too was machine-gunned. I managed to crawl out and took off my white uniform, because I was told that men in whites were targets. I then climbed under a large thorny bush . . . for some reason I felt much safer at this point than I had during the entire attack.' For most of the men at Kaneohe, there was little else they could do but take cover until the devastating assault had passed.

Chief Ordnanceman John William Finn, a Navy veteran of 15 years service, was in charge of looking after the squadron's machine-guns at Kaneohe, but Sunday 7 December was his rest day. The sound of machine-gun fire awoke him rudely.

Maddened by the scene of chaos and devastation that he saw, he set up and manned both a .30-cal. and a .50-cal. machine-gun in a completely exposed section of the parking ramp, despite the attention of heavy enemy strafing fire. He later recalled: 'I was so mad I wasn't scared'. Finn was hit several times by bomb shrapnel as he valiantly returned the Japanese fire, but he continued to man the gun, as other sailors supplied him with ammunition. John Finn was later awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for his valor and courage beyond the call of duty in this action. Even after receiving some first aid treatment, he insisted on returning to his post to supervise the re-arming of the returning PBYs that had escaped the devastation at Kaneohe.

Fifteen-year-old sailor Martin Matthews of Shelbyville, W. Va., shouldn't have been on the USS Arizona on Dec. 7, 1941. Assigned to nearby Ford Island Naval Station, Matthews was on board the Arizona to visit an old buddy, Seaman 1st Class William Stafford, en route to some sightseeing on shore.

Like the other crews in Pearl Harbor that fateful morning, the sailors of the Arizona were on the deck for morning colors and the singing of "The Star-Spangled Banner." According to most reports, the crew members did not move until the last note was sung, as usual -- despite the billowing columns of smoke across the water and the thundering Japanese gunfire. Pearl Harbor was under attack. It took Japanese planes less than 15 minutes to break the back of the enormous USS Arizona. While some witnesses recall at least one other torpedo hit, it was one bomb, from decorated Japanese bombardier Petty Officer Noboru Kanai's plane, that penetrated the main deck. "I think the second bomb that hit was close to the aft deck that I was on . . . it scared the living hell out of me," Matthews said.

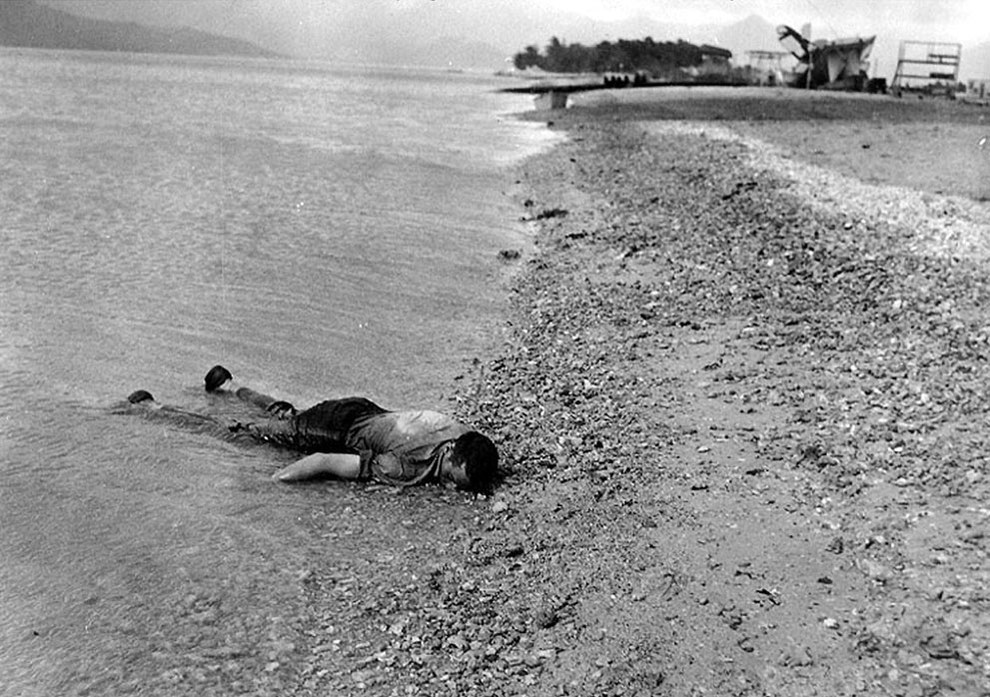

Matthews was blown overboard by the explosion, still in the dress whites he'd donned for sightseeing. "There were steel fragments in the air . . . and pieces of bodies." He swam to a mooring buoy and clung to it through the rest of the attack.

Henry A. Lachenmayer, of Oxon Hill, Md., U.S.S. Pennsylvania

"At exactly three minutes of eight, looking over toward the Naval Air Station on Ford Island, we could see a group of planes proceeding gently from a high altitude and then leveling off about 150 feet from the ground.

To our unsuspecting eyes it was just another drill, though it was somewhat peculiar that they would pick Sunday morning for maneuvering. Not until we saw the flames shoot out of the large hangar at the head of the small island did we realize the significance of the situation.

Lachenmayer scrambled to reach his battle station, where he helped put out a fire ignited by an explosion in the main deck and in the case mate, the enclosure where anti-aircraft shells were stored.

A plane that looked half like a Stuka and half like one of our own dive bombers was just leveling off and I could see the bombs dropping out of its bottom. It was a silver-gray plane with a reddish gold ball or sun painted on its side. I still don't know how I got my instrument in my case and back to the shelf in the band room but I must have made Superman's speed look amateurish. By this time all hands were manning their battle stations and I proceeded towards mine, stopping on the way to get my gas mask.

I returned to my station and found work enough; a fire had broken out on the second deck and had to be attended to with haste. . . .

The fire was precipitated by the bursting of a 500-pound bomb in the case mate and the main deck. The havoc created by this one bomb hit can never be exaggerated.

All our fire extinguishers were used up in no time. . . . Due to the cooperation of all hands concerned, the fire was eventually put out.

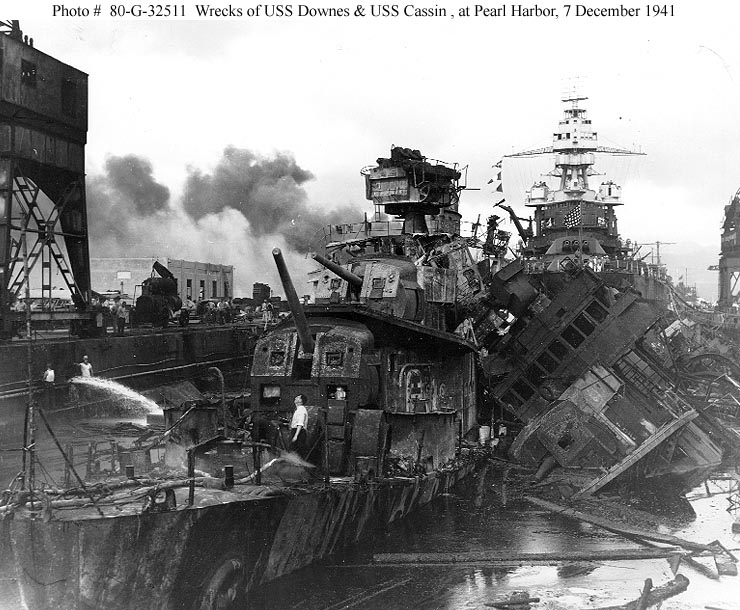

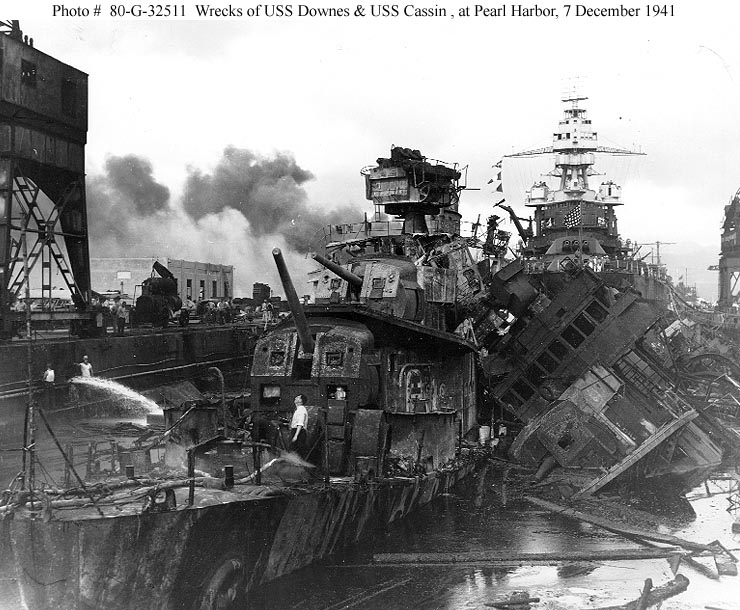

Ahead of us in dry dock were two destroyers also under repair, despite their wonderful barrage and cooperation; (they fought like wild cats) a number of bomb hits were scored and their crews were forced to abandon. . . .

Directly aft of us, moored at ten-ten dock, were the U.S.S. Oglala and the U.S.S. Helena. These two vessels, the former a mine layer and the latter one of our latest 10,000-ton cruisers, were tied or moored together. An enemy torpedo plane headed directly for the Oglala . . . and launched its torpedo. The old ship, severely injured, immediately turned on its side, and sank.

On the other side of the harbor . . . our battleships were receiving a merciless pounding. The U.S.S. Arizona received two bomb hits amidship and a great number of torpedoes. She split in half and her forward magazines burst. Directly forward of her, the U.S.S. Oklahoma received many torpedo hits and capsized.

Next to her the U.S.S. West Virginia received a tremendous amount of bomb hits and her whole port battery was wiped out. . . . The U.S.S. Tennessee stood up fairly, or rather, remarkably well considering the pounding she took. The U.S.S. Maryland stood as solid as a piece of granite and fought the enemy. She remained in one piece.

Directly forward of the Maryland, though some distance away . . ., the U.S.S. California received torpedo hits and listed on her port side. The U.S.S. Nevada, in a daring attempt to reach the open sea through the channel, was torpedoed and her wary skipper grounded her on the right side of the harbor in order to keep the channel clear.

One destroyer in the floating dry dock on our starboard was hit and went on fire, burning right at the bridge.

Now to the casualties, and I write this with a heavy heart. On our own ship, the one bomb hit pierced the boat deck abreast of No. 7 A.A. gun and tore through the No. 9 case mate and down to the main deck. All this area exploded with vigor. The Marine division suffered the severest losses.

First Lieutenant Craig, standing near the three-inch gun, had both legs blown off and received other injuries; he died almost on the spot.

Doctor Rall, a lieutenant junior grade, and a pharmacist's mate were mangled and killed instantly. This information I received from one of the musicians, Andrew Lambert, who, standing near by, saw it happen and was shell-shocked. His fellow stretcher bearer, Musician S.W. Craig, survived with minor injuries.

I wandered around the dressing station, my eyes not believing what they saw. I gave a drink here and loosened an article of clothing there; there was not much else I could do.

Many were badly burned and screamed for relief of pain; they had already received drug injections, and a glass of water to the lips was in many cases the only human assistance possible."

May their histories and stories never be forgotten.

Gordon Jones and his brother Earl had been stationed at Kaneohe on December 2 1941, and yet only five days later they were to have their baptism of fire. Between the first and second wave, they were kept busy trying to extinguish fires and moving less damaged planes to safer locations. When it began, they had no reason to suspect that the second wave would be any different to the first.

Gordon recalls: 'When this new wave of fighters attacked, we were ordered to run and take shelter. Most of us ran to our nearest steel hangar . . . this bomb attack made us aware that the hangar was not a safe place to be . . . several of us ran north to an abandoned Officer's Club and hid under it until it too was machine-gunned. I managed to crawl out and took off my white uniform, because I was told that men in whites were targets. I then climbed under a large thorny bush . . . for some reason I felt much safer at this point than I had during the entire attack.' For most of the men at Kaneohe, there was little else they could do but take cover until the devastating assault had passed.

Chief Ordnanceman John William Finn, a Navy veteran of 15 years service, was in charge of looking after the squadron's machine-guns at Kaneohe, but Sunday 7 December was his rest day. The sound of machine-gun fire awoke him rudely.

Maddened by the scene of chaos and devastation that he saw, he set up and manned both a .30-cal. and a .50-cal. machine-gun in a completely exposed section of the parking ramp, despite the attention of heavy enemy strafing fire. He later recalled: 'I was so mad I wasn't scared'. Finn was hit several times by bomb shrapnel as he valiantly returned the Japanese fire, but he continued to man the gun, as other sailors supplied him with ammunition. John Finn was later awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for his valor and courage beyond the call of duty in this action. Even after receiving some first aid treatment, he insisted on returning to his post to supervise the re-arming of the returning PBYs that had escaped the devastation at Kaneohe.

Fifteen-year-old sailor Martin Matthews of Shelbyville, W. Va., shouldn't have been on the USS Arizona on Dec. 7, 1941. Assigned to nearby Ford Island Naval Station, Matthews was on board the Arizona to visit an old buddy, Seaman 1st Class William Stafford, en route to some sightseeing on shore.

Like the other crews in Pearl Harbor that fateful morning, the sailors of the Arizona were on the deck for morning colors and the singing of "The Star-Spangled Banner." According to most reports, the crew members did not move until the last note was sung, as usual -- despite the billowing columns of smoke across the water and the thundering Japanese gunfire. Pearl Harbor was under attack. It took Japanese planes less than 15 minutes to break the back of the enormous USS Arizona. While some witnesses recall at least one other torpedo hit, it was one bomb, from decorated Japanese bombardier Petty Officer Noboru Kanai's plane, that penetrated the main deck. "I think the second bomb that hit was close to the aft deck that I was on . . . it scared the living hell out of me," Matthews said.

Matthews was blown overboard by the explosion, still in the dress whites he'd donned for sightseeing. "There were steel fragments in the air . . . and pieces of bodies." He swam to a mooring buoy and clung to it through the rest of the attack.

Henry A. Lachenmayer, of Oxon Hill, Md., U.S.S. Pennsylvania

"At exactly three minutes of eight, looking over toward the Naval Air Station on Ford Island, we could see a group of planes proceeding gently from a high altitude and then leveling off about 150 feet from the ground.

To our unsuspecting eyes it was just another drill, though it was somewhat peculiar that they would pick Sunday morning for maneuvering. Not until we saw the flames shoot out of the large hangar at the head of the small island did we realize the significance of the situation.

Lachenmayer scrambled to reach his battle station, where he helped put out a fire ignited by an explosion in the main deck and in the case mate, the enclosure where anti-aircraft shells were stored.

A plane that looked half like a Stuka and half like one of our own dive bombers was just leveling off and I could see the bombs dropping out of its bottom. It was a silver-gray plane with a reddish gold ball or sun painted on its side. I still don't know how I got my instrument in my case and back to the shelf in the band room but I must have made Superman's speed look amateurish. By this time all hands were manning their battle stations and I proceeded towards mine, stopping on the way to get my gas mask.

I returned to my station and found work enough; a fire had broken out on the second deck and had to be attended to with haste. . . .

The fire was precipitated by the bursting of a 500-pound bomb in the case mate and the main deck. The havoc created by this one bomb hit can never be exaggerated.

All our fire extinguishers were used up in no time. . . . Due to the cooperation of all hands concerned, the fire was eventually put out.

Ahead of us in dry dock were two destroyers also under repair, despite their wonderful barrage and cooperation; (they fought like wild cats) a number of bomb hits were scored and their crews were forced to abandon. . . .

Directly aft of us, moored at ten-ten dock, were the U.S.S. Oglala and the U.S.S. Helena. These two vessels, the former a mine layer and the latter one of our latest 10,000-ton cruisers, were tied or moored together. An enemy torpedo plane headed directly for the Oglala . . . and launched its torpedo. The old ship, severely injured, immediately turned on its side, and sank.

On the other side of the harbor . . . our battleships were receiving a merciless pounding. The U.S.S. Arizona received two bomb hits amidship and a great number of torpedoes. She split in half and her forward magazines burst. Directly forward of her, the U.S.S. Oklahoma received many torpedo hits and capsized.

Next to her the U.S.S. West Virginia received a tremendous amount of bomb hits and her whole port battery was wiped out. . . . The U.S.S. Tennessee stood up fairly, or rather, remarkably well considering the pounding she took. The U.S.S. Maryland stood as solid as a piece of granite and fought the enemy. She remained in one piece.

Directly forward of the Maryland, though some distance away . . ., the U.S.S. California received torpedo hits and listed on her port side. The U.S.S. Nevada, in a daring attempt to reach the open sea through the channel, was torpedoed and her wary skipper grounded her on the right side of the harbor in order to keep the channel clear.

One destroyer in the floating dry dock on our starboard was hit and went on fire, burning right at the bridge.

Now to the casualties, and I write this with a heavy heart. On our own ship, the one bomb hit pierced the boat deck abreast of No. 7 A.A. gun and tore through the No. 9 case mate and down to the main deck. All this area exploded with vigor. The Marine division suffered the severest losses.

First Lieutenant Craig, standing near the three-inch gun, had both legs blown off and received other injuries; he died almost on the spot.

Doctor Rall, a lieutenant junior grade, and a pharmacist's mate were mangled and killed instantly. This information I received from one of the musicians, Andrew Lambert, who, standing near by, saw it happen and was shell-shocked. His fellow stretcher bearer, Musician S.W. Craig, survived with minor injuries.

I wandered around the dressing station, my eyes not believing what they saw. I gave a drink here and loosened an article of clothing there; there was not much else I could do.

Many were badly burned and screamed for relief of pain; they had already received drug injections, and a glass of water to the lips was in many cases the only human assistance possible."

Last edited: