A Life Aloft

Well-Known Member

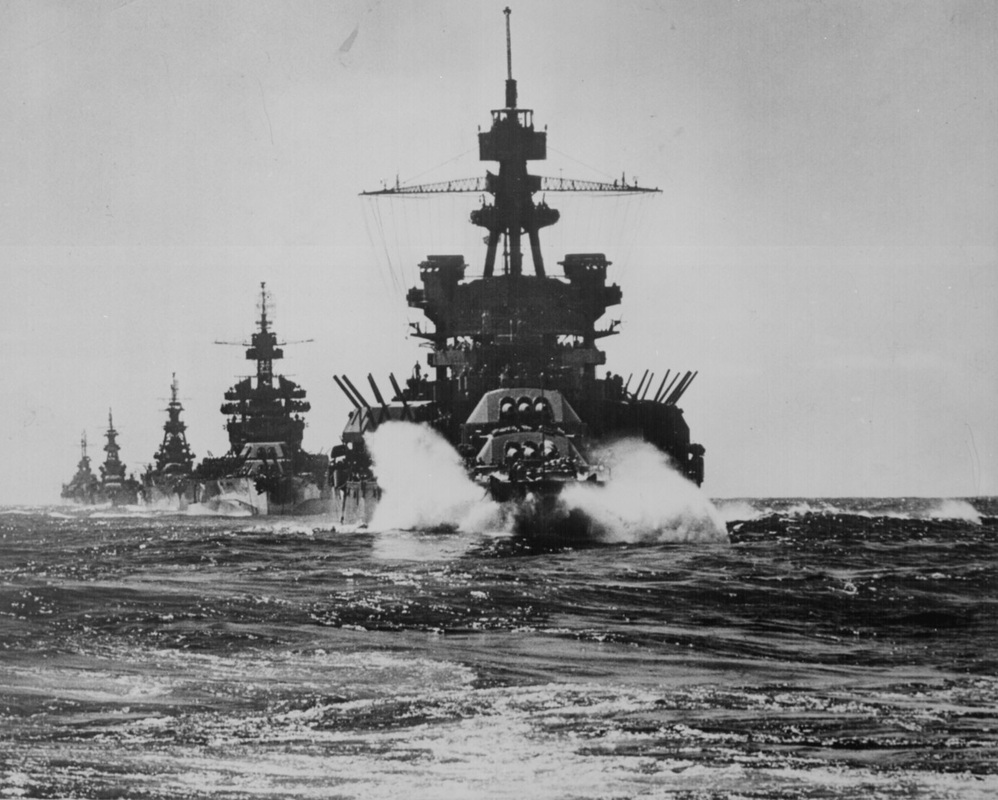

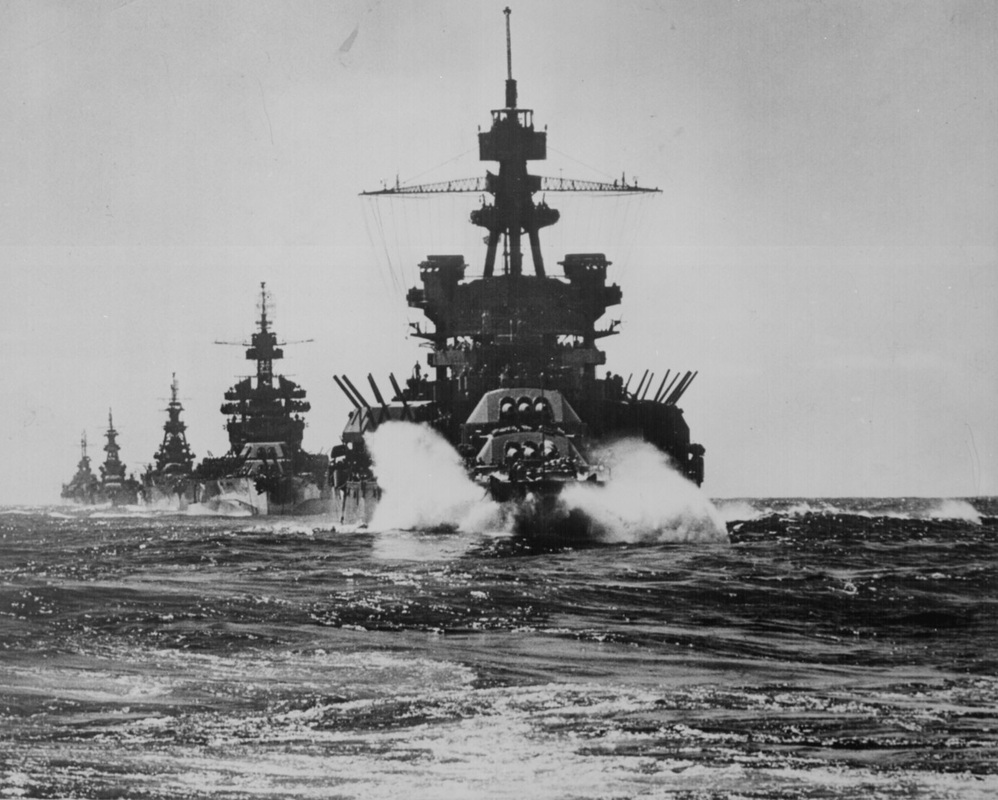

This week marks the 76th Anniversary of the Battle of Midway which is recognized as the "turning point of the Pacific." Against all odds and being heavily outnumbered, it was the Allies' first major Naval victory against the Japanese.

USS Yorktown

USS Enterprise

USS Hornet

Six months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the United States defeated Japan in one of the most decisive naval battles of World War II. Thanks in part to major advances in code breaking, the United States was able to preempt and counter Japan’s planned ambush of its few remaining aircraft carriers, inflicting permanent damage on the Japanese Navy. The Battle of Midway is known as turning point in the Pacific campaign, the victory allowed the United States and its allies to move into an offensive position.

This fleet engagement between U.S. and Japanese navies in the north-central Pacific Ocean resulted from Japan’s desire to sink the American aircraft carriers that had escaped destruction at Pearl Harbor. Admiral Yamamoto Isoroku, Japanese fleet commander, chose to invade a target relatively close to Pearl Harbor to draw out the American fleet, calculating that when the United States began its counterattack, the Japanese would be prepared to crush them. Instead, an American intelligence breakthrough and the solving of the Japanese fleet codes, enabled Pacific Fleet commander Admiral Chester W. Nimitz to understand the exact Japanese plans. Nimitz placed available U.S. carriers in position to surprise the Japanese moving up for their preparatory air strikes on Midway Island itself.

The Japanese carriers were caught while refueling and rearming their planes, making them especially vulnerable. The Americans sank four fleet carriers–the entire strength of the task force.....Akagi, Kaga, Soryu, and Hiryu, with 322 aircraft and over five thousand sailors. The Japanese also lost the heavy cruiser Mikuma. American losses included 147 aircraft and more than three hundred seamen.

Former U.S. Navy Master Chief Deen Brown, center, with Capt. Paul Whitescarver, Commander of the U.S. Naval Submarine Base New London, left, and Command Master Chief Cary Carroll of the Naval Submarine Support Center, place a wreath in memory of those lost in battle as navy personnel mark the 76th anniversary of the WWII Battle of Midway, Monday, June 4, 2018, at the Submarine Force Library and Museum in Groton. Brown was a radioman on the submarine USS Trout which was on patrol around the battle.

Vice Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Bill Moran salutes a wreath during the Battle of Midway 76th Anniversary Commemoration Ceremony at the U.S. Navy Memorial.

USS Yorktown

USS Enterprise

USS Hornet

Six months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the United States defeated Japan in one of the most decisive naval battles of World War II. Thanks in part to major advances in code breaking, the United States was able to preempt and counter Japan’s planned ambush of its few remaining aircraft carriers, inflicting permanent damage on the Japanese Navy. The Battle of Midway is known as turning point in the Pacific campaign, the victory allowed the United States and its allies to move into an offensive position.

This fleet engagement between U.S. and Japanese navies in the north-central Pacific Ocean resulted from Japan’s desire to sink the American aircraft carriers that had escaped destruction at Pearl Harbor. Admiral Yamamoto Isoroku, Japanese fleet commander, chose to invade a target relatively close to Pearl Harbor to draw out the American fleet, calculating that when the United States began its counterattack, the Japanese would be prepared to crush them. Instead, an American intelligence breakthrough and the solving of the Japanese fleet codes, enabled Pacific Fleet commander Admiral Chester W. Nimitz to understand the exact Japanese plans. Nimitz placed available U.S. carriers in position to surprise the Japanese moving up for their preparatory air strikes on Midway Island itself.

The Japanese carriers were caught while refueling and rearming their planes, making them especially vulnerable. The Americans sank four fleet carriers–the entire strength of the task force.....Akagi, Kaga, Soryu, and Hiryu, with 322 aircraft and over five thousand sailors. The Japanese also lost the heavy cruiser Mikuma. American losses included 147 aircraft and more than three hundred seamen.

Former U.S. Navy Master Chief Deen Brown, center, with Capt. Paul Whitescarver, Commander of the U.S. Naval Submarine Base New London, left, and Command Master Chief Cary Carroll of the Naval Submarine Support Center, place a wreath in memory of those lost in battle as navy personnel mark the 76th anniversary of the WWII Battle of Midway, Monday, June 4, 2018, at the Submarine Force Library and Museum in Groton. Brown was a radioman on the submarine USS Trout which was on patrol around the battle.

Vice Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Bill Moran salutes a wreath during the Battle of Midway 76th Anniversary Commemoration Ceremony at the U.S. Navy Memorial.