SteveCostello

My member is well-known.

Out of curiosity, what are the lateral separation rules for aircraft approaching parallel runways?

Out of curiosity, what are the lateral separation rules for aircraft approaching parallel runways?

Oh... I know. Not to mention the fact that the flight paths are not convergent. I just wanted to compare that separation mandate from the separation these guys had.I don't know the answer to that, but I do know the reason for the reduced minima. Radar update rate, and area (like square miles) of controller responsibility. Also, the resolution of an enroute controller's scope is much much lower than that of a final approach controller's scope.

what you guys do for normal ops is 100% unacceptable to airline ops.

Seriously? You believe there is 0% applicability? There's no airmanship or judgment aspects, or situational awareness, that are being built in all of that high performance maneuvering?

Horsepucky.

If that were the case, then no tactical background pilots would ever be hired at 121 operations.

C'mon, you know that's not what he's saying.

C'mon, you know that's not what he's saying.

I still find it an eye-roller that so many pilots see this incident as a "seconds from death" issue.

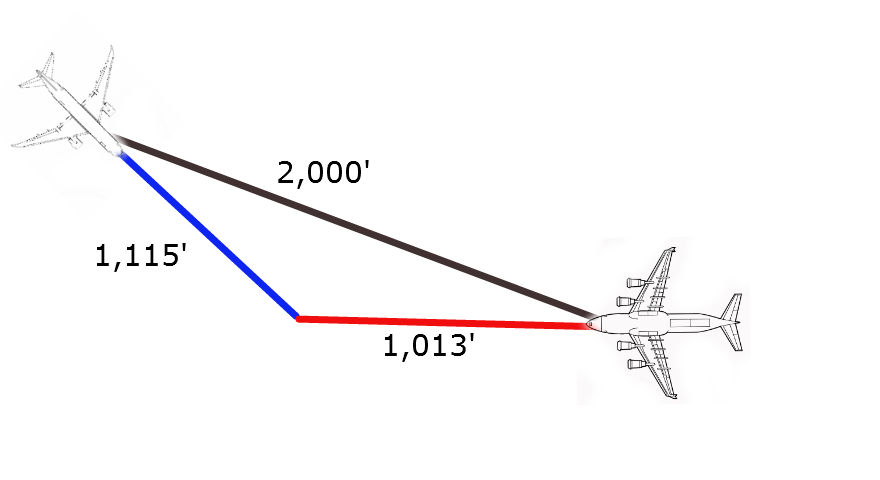

... I still find it an eye-roller that so many pilots see this incident as a "seconds from death" issue. ... I still maintain that 2000' of separation -- lateral or vertical -- does not constitute a "near midair" as described in the thread title, regardless of if the FAA defines it that way or not.

I think at flight level while crossing the ocean you are out of the see and avoid phase of flight and are in the fat dumb and happy phase.

I have roughly the same amount of experience with TCAS. All of it being TCAS II and most of that with change 7. While I fully agree it can give false targets and not refresh fast enough to spot traffic. When it comes to deconflicting two aircraft, it does a tremendous job. It pretty much saved our bacon comming out of OXR last week. Some one was sneaking out of the LA Class B as we were level at 5,000 doing 250kts. We were busy trying to find previously called traffic. All of sudden he flips on his tansponder, twelve o'clock, same alt, opposite direction, less than a mile. As we see him on TCAS, and start to look, it gives us the descend RA. At the same time, he pops up on Mugu's radar while we're in the middle of the RA. He came across the top of us, head on at about 500ft, never even knew we were there. That all happened in about 30 seconds. We were both heads up looking out the front for traffic and I really don't think we would have seen him. Small piper head on, not moving laterly, makes for a small target.I know what most FOMs say, and what the FAA recommends. I'm not advocating to regularly just blow off RAs. Hell, I'm not even advocating to do it every once in a while. Probably not even 1 out of 1,000 times in the operating environment that most of you are talking about (I'm completely excluding my operating environment because it obviously does not apply in any way to commercial operations in the US NAS or even ICAO airspace).

What I am saying is that if pilots are merely a slave to what the TCAS container is saying -- both in terms of data displayed as well as commands issued -- and not using all the tools available to build their SA and then operating their aircraft appropriately, then that is what is crazy.

With respect to "exact science", all I can say is that I have about 6 years experience flying TCAS I and II-equipped aircraft (both slow and fast movers), and I have seen it be less than precise on numerous occasions. Mostly they were displayed errors in both azimuth and altitude, and calls for RAs based on predicted maneuvering out of the other aircraft that never happened or happened differently than predicted. Or, it was displays not showing aircraft that were squawking, or the opposite -- showing phantom traffic that did not exist. In the fighters, especially, we were the ones messing with the TCAS-equipped aircraft and causing them to get all hot and bothered; TCAS doesn't predict the speeds and climbing / maneuvering capability of a fighter, and because the system lags, we could be setting off RAs even when we weren't remotely any conflict for the other aircraft. More than once I have had aircraft climb or turn into me while following an RA -- a situation where I saw them the entire time, and they obviously did not see me.

As an aside, in fighter and combat operations, I give TCAS even less importance in my SA heirarchy for a number of reasons. Let's not forget that TCAS is trying to maintain some relatively large miss distances between aircraft as well as command relatively smooth and light G maneuvering to do it. In a potentially very crowded environment (for example, a 'stack' over a target where aircraft are at 500-foot altitude increments doing circles of various radii, speeds, and directions) and filled with non-squawing aircraft (like every #2 of a formation), not only does TCAS sometimes try and make me climb/descend into someone else's airspace to 'avoid' someone who is not going to hit me because of established altitude deconfliction, but it also doesn't see all of the idiotic wingmen out there who are moseying around at other-than-their-assigned-altitude and not even appearing on the TCAS display. In that situation, I go to STBY or TA, and only use the display for helping get my eyes on something I haven't been able to pick out of the sky yet visually. So, for the purposed of this discussion, I'm completely disregarding those types of experiences because we just don't see that in common carrier operations.

Again, look at the conflicting commands seen in this exact situation and look at the lines on the admittedly non-scientific map posted -- there's direct evidence that the system isn't perfect. Even if we flew in a perfect world where every aircraft was flying around with a TCAS II or better system on board (and obviously we know that is far, far from the truth), this would not be a perfect system. Bearing in mind that there are a whole crap-ton of aircraft operating in the National Airspace System that aren't so well equipped, then it's just not possible to christen the system as the Saviour. Is it good? Yep. Does it provide value? Absolutely -- I think it's a magnificent system and I really like flying aircraft that are so equipped. In no way, though, does it replace my duty as an aviator to clear my flightpath, nor does it replace my responsibility to build and maintain SA, and respond appropriately to possible conflicts. TCAS is a single piece of information in building that SA.

But, hey -- if the FAA's printed information on it says it's perfect and precise, then I guess it is, right?

Out of curiosity, what are the lateral separation rules for aircraft approaching parallel runways?

Not sure about military separation standards, but here's how I gauge it.

If we get a TA, it's fairly uncommon, and enough to make you perk up and pay attention

If it gets to the RA stage, multiple levels of safety have failed, and TCAS had to step in to prevent an accident.

The only time I wouldn't consider an RA event as serious is if I 100% positively have the traffic in sight, and I'm manoeuvring accordingly. That wasn't the case in this incident.